How can colour psychology be used to good effect in design and architecture?

Colour psychology is often thought of for its use in company branding, logo design, and interior design, but there are many applications.

In choosing colours for a brand, for example, companies want their chosen colours to reflect their personality, and to evoke certain feelings in their target market; though, it’s more about choosing the right colours that fit with how the brand wants to be perceived than it is about choosing a colour that will have a certain effect.

Green, for example, is often thought of as calming, but Greenpeace use it to particular effect to represent nature and the environment.

If you really don’t think colour can make a difference to how a brand is perceived, imagine a fresh, green smoothie or crisp lettuce packaged in an oily black bag, with ashen grey highlights. That’s not nearly so appealing or taste bud tingling as green packaging that evokes the contents and gives an impression of freshness and taste appeal. You can bet black packaging would reduce sales.

Or think about a brand like Heckler & Koch, who make guns. They use reds, black and white to show off their products (https://www.heckler-koch.com/en/products/sport.html). Try imagining a glittery, baby pink version of that ad. It really doesn’t work, does it?

What is colour psychology and how does it work?

Colour psychology is simply the effect that colour can have on the mental and emotional state of the human brain.

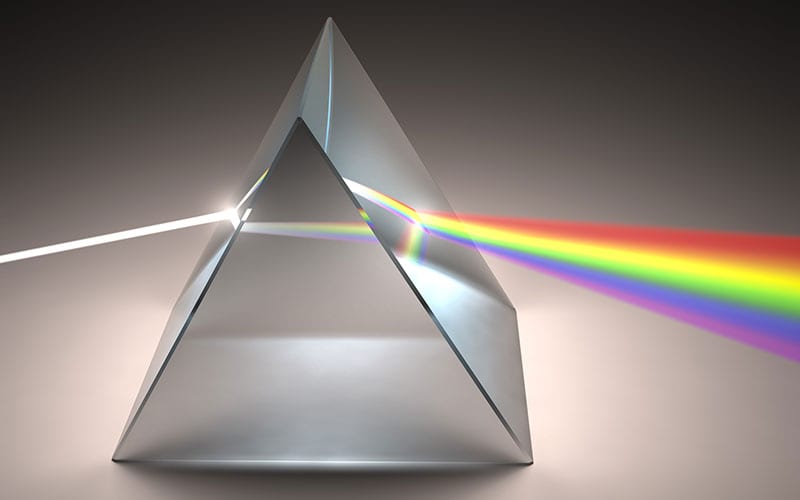

It’s well known that Sir Isaac Newton discovered that passing white light through a prism would split it into the visible colour spectrum. He also discovered that each individual colour can’t be broken down any further into other colours, but can be combined to produce different colours – yellow mixed with red will create orange, for example.

One other extremely important discovery which definitely has implications for how colour is used is that some colours, such as magenta and green, will cancel each other out and produce white light.

Despite the fact that these experiments were done in 1666, remarkably little has been done in the field of colour psychology to scientifically prove what effects colour can have on the human brain.

There are some assumptions that are often trotted out by branding agencies or other designers, for example, that blue will make people feel calm, and that red will excite them, but our reaction to colour is subjective. If you hate blue and prefer not to see it, you certainly won’t find it calming.

Colour meanings can also change depending on culture. For example, white tends to mean purity, cleanliness and innocence in the west but is a colour of mourning in many countries in the east.

So, it’s not so much that individual colours can programme our minds like a computer and reliably make everyone feel specific emotions, but they can have some effect on our mood, and our perception of brands, brighten up an interior or add grandeur or a feeling of space and energy to an architectural build.

Uses of colour and light in architecture are similar to how they are used in branding, in that the right colours can add to the ‘personality’ of a building, as much as they can add to a brand’s personality, and influence how people feel when spending time in the space.

“The importance of architecture as a trigger to physical, physiological and psychological wellbeing is nowadays becoming a topic of significant relevance.” – Dr Sergio Altomonte, Professor at Nottingham University.

Colour psychology in interior design

We’ve all heard the term ‘sick building syndrome’ and while many of its causes might be put down to volatile organic compounds (VOCs), poor ventilation, and poor lighting, colour can also make a huge difference to how people feel when they are inside a building.

In one town hall in the UK, which shall remain nameless, they recently redesigned their benefits department. This could have been a good thing, and a chance to create a light and airy space which would have been a wonderful working area for their staff, and at the very least, a pleasant space to visit for claimants at what can be a very stressful time.

Their original office was light wood panelled, with plenty of light coming in through a beautiful glass ceiling, neutral paint colours, and a warm, chocolate coloured carpet.

Somehow, in their ‘wisdom’, the planning department for this project managed to produce a dark grey walled and floored, depressing monstrosity with clashing red, orange and burgundy ‘highlights’, and strip lighting that was alternately blinding or too dark, depending on where you were sitting. The only natural light in the office came from the double-doored entrance.

The atmosphere shifted from cheerful, relaxing and calming in the first design, to vault-like, dank and depressing in the new one, with staff, unsurprisingly, reporting headaches, and visitors complaining about how awful the new look was and how bad it made them feel when they entered the building.

A backwards step, and one that could have been avoided, simply by planning better for colour and light use in the office.

“The study of colour is essentially a mental and psychological science, for the term colour itself refers to sensation.“ – Faber Birren, author of ‘Colour psychology and colour therapy: a factual study of the influence of colour on human life’.

When interior designers plan out their designs, they don’t just pick colours that their clients like and use those, they look at each room individually and think about what times of day the room will be used, what the room is for, and how long people will spend in it. Only then do they think about the mood and the feel they’d like to introduce.

Before they start a design, they also consider the natural light entering the room, and when, or if, the sun shines into the room over the course of the day. Natural light from outside can completely change the look of applied colours on the walls, and change a design to something that wasn’t intended at all.

Another consideration is the size of the room. Designers know to use lighter colours in small rooms to give a feeling of space, and that darker colours can bring a large room in and make it feel cosy.

Colour can also have an effect on the perceived temperature of a room, with cold colours, such as blues, seeming to take the temperature down, and warm colours having enough of an effect that the same room at the same temperature can feel warmer.

“Colour rings the doorbell of the human mind and emotion and then leaves.” – Faber Birren.

Colour psychology in design and architecture

When designing anything, whether a product that fits in the hand, or an entire city, the designer or the architect must consider what the final product of their labours will be used for, who by, how often and, in the case of buildings, how the flow of people entering and exiting a building will work.

One word that’s often bandied about in the design field is ergonomics – “the study of people’s efficiency in their working environment”, and while that is, of course, incredibly important, one other consideration is actually ‘colour’ ergonomics.

The architect has to choose colours, knowing what sensory responses are likely from people using that environment, and select colours that will have the best possible effect.

Imagine a prison painted in bright, stimulating, aggressive reds and oranges, or a hospital wing where patients need rest and recovery done out in the same gaudy, clashing colours.

Picture a children’s playroom at the hospital done in drab greys, black, pale greens and muted colours.

None of those colour choices are in the least bit appropriate for the surroundings or for the people and could have a deleterious effect on the atmosphere and the likelihood of increased fights in prison, and lack of recovery among patients.

Colour really does matter enormously, and it can’t be an afterthought, tacked on at the end of a design, without full consideration of its impact on the people who use the building.

Outside use of colour

Colour design isn’t just restricted to the interior designer’s job of creating a mood with paints, fabrics and furniture.

With modern materials and finishings, such as alsecco’s façade finishes (https://www.alsecco.co.uk/facade-finishes/), building exteriors can be designed to match their interiors and reflect the inside personality and feel of the building outside.

With beautiful designs of coloured glass, metals, bricks, tiles, different textures and finishes, buildings can now use colour to stand out among the other buildings in the city and attract the eye.

Going back to that grey and drab children’s hospital play room, imagine instead vibrant bursts of colour on the walls, different materials and surfaces to play on that are soft and cushioning for safety, and an outside play area that continues the interior design with bright swings and slides, coloured benches, vibrant and stimulating tiles on the walls, and an atmosphere of fun and enjoyment. The difference in feel and atmosphere is palpable between the two designs, with the chance of recovery so much higher in the second design. And all that’s really changed is the colours.

Imagine that prison building with calming and pleasant blues and greens on the walls, with natural light to alleviate depression and help inmates to cope better. While we’re not suggesting prisons should in any way be designed like country houses, neither should they be neglected. As with any other building, they should be designed fit for purpose, and to suit the people who will be using them, and that includes colour choices that help the inmates, rather than hinder them.

Even better, if urban planning is being done from scratch, buildings, walkways, roads and open squares can all be built to have a beautiful, flowing, coherent design that pleases the eye, and eases the flow of people through the city, offering stunning design that is visually intriguing, with a variety of colours, textures and materials.

Colours could be chosen to subtly influence mood depending on the use of the outside space, for example, brighter colours to stimulate the appetite in a food court, or calmer mood colours to slow people down and get them to relax in busier areas.

Colours could be put in place to subtly direct people on through the shopping complex, to indicate different areas of use, such as warm colours and enticing chocolate shades for the artisanal bakery and chocolate shop area, and vibrant, busier colours in the high fashion section. With the right planning, an architect can use colours to create a stunning, dynamic and inviting shopping experience that has visitors coming back again and again.

Nowadays, architects and designers have far more information available to make good colour decisions, and with the advent of Building Information Modelling (BIM) software, designs can be checked and double-checked at every step to confirm that they are having the desired effect.

BIM can include the attributes of each object in the design, including furniture, and the paint on the walls. With BIM, you can run a check to see what will happen if you change even one single item in a room. You can look at the colour you’ve picked to paint the walls and see if it works with the light coming in through the windows at all times of day, check if it will match the furniture and see if the rug you chose for that corner will go with the rest.

Building exteriors can also be modelled before any building work is done and materials ordered, to check whether the glass tile finish you were going to pick for the outside will badly affect any other buildings in the area by producing glare. You can see how your building will look before it is finished, and place it in the city’s surrounding buildings to see how it will fit in with what is already there.

BIM gives architects and designers the chance to test every aspect of their designs, from materials and light to colour, and resolve any problems before coming up against them in the building process, when money has already been spent.

With tools like that to hand and a wider choice of excellent materials available, use of colour both internally and externally for buildings can only improve, improving our environment, and both living and working spaces along with it.

“The impact architecture has on a person’s mood is huge. Arguably these are the fundamentals of architecture: not how it looks, but how we feel it, through the way it allows us to act, behave, think and reflect,” – Dr Melanie Dodd, Central St Martins Art School.